Introduction: The Mad Scientist of Reggae

Lee “Scratch” Perry was a tough person to define. Depending on who you asked, he was a madman, a prophet, or a musical genius. Sometimes he embodied all three in a single day. Perry undoubtedly altered the direction of current music, dub, and reggae. While Bob Marley’s voice introduced reggae to the world, Perry’s imagination reshaped sound into unique, cosmic forms still felt today.

Born Rainford Hugh Perry in the rural Jamaican parish of Hanover in 1936, he grew up in poverty, always restless and tinkering with rhythm, sound, and language. When he arrived in Kingston, he had the energy of a trickster and the mind of a scientist. What followed was a career more mythical than historical: building his Black Ark studio, producing early Wailers tracks, inventing strange recording techniques, and burning it all down—literally and figuratively—only to rise again.

Perry wasn’t just an eccentric producer muttering incantations into a microphone. He had a significant impact on contemporary music. His influence may be found in many genres, including hip-hop, punk, and electronic bass.

I. From Street Corners to Studio Control Rooms

Early Kingston Days

When Perry first arrived in Kingston in the 1950s, he took any job he could find, even paving roads. Joking that he learned rhythm from the task, he mentioned how he was able to comprehend beats per minute by listening to the sound of stones hitting gravel. Whether that is true or not, he soon assimilated into Kingston’s expanding sound system culture.

He got his first big break with Clement “Coxsone” Dodd at Studio One. At first, Perry acted more like a hustler than a technician—running errands, selling records, and eventually moving into production.

He also had a talent for confrontation. Nicknamed “Scratch” after a song he recorded called “Chicken Scratch,” Perry built a reputation for being brilliant but difficult to manage. When arguments with Dodd intensified, he moved on and teamed up with producer Joe Gibbs. That partnership also ended in fiery disagreements. Perry often followed this pattern: he would help revolutionize a studio or label, then leave after clashing with its leaders.

Birth of “The Upsetter”

By the late 1960s, Perry decided to go solo and launched his Upsetter label. His first big hit, “People Funny Boy,” was not just important musically—it also directly insulted Joe Gibbs. With a crying baby sound effect and a jagged rhythm, it announced Perry’s confrontational, experimental style, always ready to mock his rivals. The record also marked the true arrival of reggae, moving away from ska and rocksteady into heavier, more syncopated rhythms.

II. The Black Ark Years: Alchemy in a Shack

Building the Ark

In 1973, Perry built his own studio in the Washington Gardens neighborhood of Kingston and named it the Black Ark. From the outside, it didn’t look impressive—just a simple home studio. However, Perry created an environment within that felt both sacred and experimental. The walls were covered in graffiti, mirrors reflected energy, and Perry often held rituals during sessions, burning incense or sprinkling water.

The Black Ark didn’t have fancy equipment; it was modest by global standards. But Perry made the most of what he had. Simple effects like tape delay and spring reverb were creatively employed on his MCI mixing board, which he exploited as a tool.

Techniques that Defied Logic

Perry was known for trying anything. He might bury mics in dirt to catch “earthy” tones or blow ganja smoke onto a tape machine. He even talked to the equipment as if it were alive. Even while these acts can appear ridiculous, they frequently resulted in amazing noises.

Instead of seeking clarity and polish, Perry wanted mystery. He added layers to recordings until they glistened with mesmerizing basslines, odd bits, and echoes. At times, he erased entire sections of tape, replacing them with odd animal noises or whispers. Critics sometimes saw his methods as chaotic, but listeners in Kingston’s sound system scene heard something different: magic.

Collaborations and Classics

During the 1970s, the Black Ark became a destination for Jamaica’s top talent. Bob Marley and the Wailers recorded important tracks there, including early versions of “Small Axe” and “Duppy Conqueror.” Perry also produced defining records for Max Romeo (“War Ina Babylon”), Junior Murvin (“Police and Thieves”), and The Congos (“Heart of the Congos”).

Each project bore his unmistakable mark: reverb-rich atmospheres, rhythm lines that felt solid, and sudden sound swirls that seemed to come from another realm.

Key Moments in Lee “Scratch” Perry’s Career

- 1950s – Moves to Kingston; joins Coxsone Dodd’s Studio One.

- 1968 – Releases “People Funny Boy,” establishing the Upsetter label.

- 1973 – Builds the Black Ark studio.

- 1976 – Produces Junior Murvin’s Police and Thieves.

- 1977 – Produces The Congos’ Heart of the Congos.

- 1983 – Burns down the Black Ark in a fit of anger and despair.

- 1990s–2000s – Gains global recognition, collaborates with international artists.

- 2021 – Lee Scratch Perry Passes away in Jamaica at age 85, leaving behind a cosmic legacy.

III. Madness, Myth, and Self-Destruction

By the early 1980s, Perry’s behavior grew more erratic. Friends remember him pacing barefoot around Kingston, scribbling symbols on walls, or speaking in riddles. Some attributed this to his heavy Ganja and rum use, others felt he simply embraced his own eccentric myth too much.

In 1983, Perry set fire to the Black Ark. The reasons are still debated. According to some, he believed that evil spirits had corrupted the studio. Some argue that it was a creative outlet, a means of dismantling what felt like a cage. Whatever the truth, the burning of the Ark marked the end of an era.

For a while, Perry seemed adrift. He moved between Europe and the U.S., recording sporadically, often producing uneven work. Yet even during his most unconventional times, he kept a loyal following. British producers in the burgeoning dub and electronic sectors saw him as a visionary, while punk bands such as The Clash heralded him as a hero.

IV. Global Reverberations

Influence on Punk and Rock

By the late ’70s, Perry’s work went global. “Police and Thieves” was famously covered by The Clash, who also invited Perry to collaborate. Punk audiences found resonance in his defiant demeanor, viewing him as a fellow opponent of the status quo.

Influence on Hip-Hop

Like King Tubby, Perry played a quiet but critical role in shaping hip-hop’s foundation. His focus on rhythm breaks, echo effects, and toasting created a model that DJs like Kool Herc built upon in the Bronx.

Influence on Electronic Music

Producers of electronic music—from jungle to dubstep to techno—have cited Perry as a direct influence. He foresaw contemporary remix culture by using the studio as an instrument. Artists like The Orb, Mad Professor, and even mainstream acts like Beastie Boys and Massive Attack drew from his sound.

Discography Highlights: Five Essential Lee “Scratch” Perry Records

- The Upsetters – Super Ape (1976)

A landmark dub album, dense with atmosphere and Perry’s playful sonic techniques. - Junior Murvin – Police and Thieves (1976)

Perry’s production turned Murvin’s falsetto anthem into a global hit. - Max Romeo – War Ina Babylon (1976)

Politically charged and spiritually rich, featuring Perry at his best. - The Congos – Heart of the Congos (1977)

Often considered Perry’s masterpiece, a deeply mystical reggae album. - Lee “Scratch” Perry – Arkology (1997)

A comprehensive retrospective box set capturing the depth of his Black Ark years.

V. Later Life and Recognition

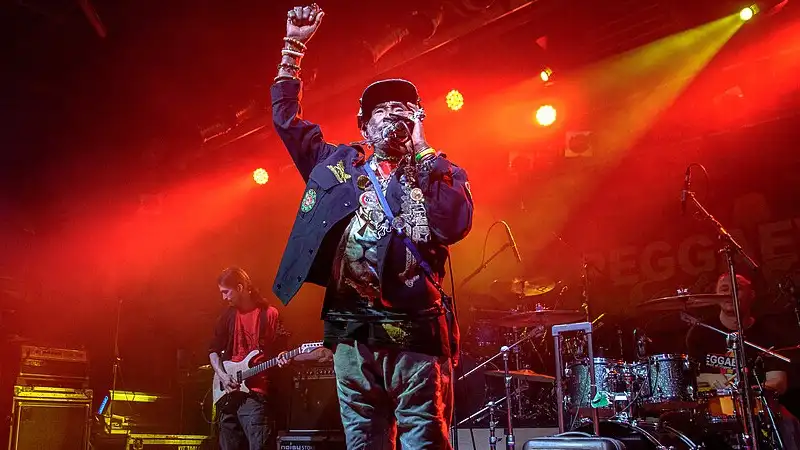

Perry rebranded himself as a world-traveling oddball in his final years. Wearing outrageous costumes dying his hair, and ever more adventurous album covers, he rose to fame as a festival mainstay. He collaborated with European producers like Adrian Sherwood and performed with a range of bands, from rock to electronic.

Some critics argued that his later work lacked the focus of his Black Ark days, while others saw his performances as living artworks—part music, part theater, part spiritual ritual.

In 2003, Perry won a Grammy for Jamaican E.T., finally earning mainstream recognition. Yet awards never defined him. As he once said, “I am not normal, I am magic.”

Conclusion: The Eternal Upsetter

Lee “Scratch” Perry was difficult to categorize, and maybe that was intentional. He thrived in contradiction: a genius and a jester, a visionary and a disruptor. His work reshaped sound possibilities, making reggae a cosmic and global force.

Even after his death, Perry’s influence remains strong. Whether you listen to a dubstep track, a hip-hop beat, or even a psychedelic rock album, you might hear a glimpse of his experiments. Like smoke drifting from the ruins of the Black Ark, his sound still lingers—mysterious, unpredictable, eternal.

People Also Ask — Lee “Scratch” Perry (FAQ)

Who was Lee “Scratch” Perry?

Lee “Scratch” Perry (born Rainford Hugh Perry, 1936–2021) was a Jamaican record producer and inventor of many dub production techniques. He was the creative force behind the Black Ark studio, mixing technical experimentation with spiritual ritual to produce records that sounded unlike anything else at the time.

What was the Black Ark Studio?

The Black Ark was Perry’s small backyard studio in Kingston, where he produced many landmark reggae and dub records in the 1970s. Though equipped with basic gear (a four-track machine and some effects), it became renowned for its layered reverb, tape echo, and unique atmosphere.

What made Lee Scratch Perry’s production style unique?

Perry preferred hands-on, often improvised methods: saturating tape, using extreme EQ, spring reverb, and odd mic placements—along with spontaneous sound effects and vocal chants. He treated the studio as an instrument and embraced “happy accidents,” prioritizing texture and mood over polish.

Which major artists did he work with?

He collaborated with key figures in reggae, including early sessions with Bob Marley & The Wailers, and full productions for Max Romeo, Junior Murvin, The Congos, and his own Upsetters band. His influence also reached punk and electronic artists who admired his darker, echo-laden sound.

Why did Lee Scratch Perry burn down the Black Ark?

Accounts differ on this. Perry provided various explanations over time—from spiritual cleansing to a desperate act during a personal crisis. The true reason remains unclear. Regardless, the fire effectively ended his most productive creative era.

How did Lee Scratch Perry influence other genres?

His dub techniques—simplifying tracks to bass and drums, using delay and reverb as compositional tools, and live reworking of recordings—shaped hip-hop DJing, punk’s embrace of reggae, and later electronic styles like dubstep and jungle. Producers across genres analyze his mixes for lessons on space and texture.

What are essential Lee Scratch Perry albums to start with?

Key records include Super Ape (The Upsetters), War Ina Babylon (Max Romeo, produced by Perry), Police and Thieves (Junior Murvin, produced by Perry), Heart of the Congos (The Congos), and the Arkology box set that collects Black Ark work. These provide a good overview of his range.

Is Lee Scratch Perry’s music still available?

Yes—many Black Ark-era releases have been reissued and are available on streaming services, vinyl reprints, and box sets. Arkology is a convenient collection for newcomers.

Was Lee Scratch Perry more mystical performance or deliberate technique?

Both. He combined ritual and showmanship with real technical experimentation. The incense, graffiti, and stories created the myth, but his use of tape, effects, and arrangement showed clear, consistent methods instead of pure chance.

Where can I learn more about his techniques?

Carefully listen to isolated Black Ark productions, especially the early mixes, and compare dubs to their vocal originals. The differences will reveal his use of echo, drop-outs, and reverb as compositional elements. Interviews, liner notes on reissues, and documentaries about Black Ark and 1970s Kingston are also great resources for deeper study.