The Formative Years: Humble Beginnings in Trenchtown

Every story in reggae history seems to trace back to Trenchtown, and The Wailers were no exception.

It wasn’t the kind of neighborhood that encouraged dreams of global fame. Sheet-metal houses leaned together, poverty pressed in from all sides, and daily survival often took priority over art. Yet Trenchtown was also a breeding ground for resilience and creativity. Kids made footballs from rags, beat rhythms on oil drums, and sang in the streets.

Amid this chaos, three young men, Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, and Bunny Wailer, began harmonizing.

They didn’t see themselves as icons then. They were just friends, voices blending in dusty yards, hinting at something bigger.

Their sound reflected Trenchtown’s toughness and its hope.

A Harmonious Trio: Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, and Bunny Wailer

The early Wailers band was defined by balance:

- Bob Marley provided a voice of raw conviction, a mix of grit and warmth.

- Peter Tosh was the militant one, unflinching in his social and political stance.

- Bunny Wailer added high, sweet harmonies that grounded the group in a spiritual calm.

Together, they weren’t just singing; they were shaping a new chapter in Wailers band history. Some argue Marley’s charisma eventually outshone the others, but at the start, the magic was undeniably in the trio’s combined energy.

The Trenchtown Community: Roots of Resilience

To understand The Wailers, you need to understand the reggae pioneers of Trenchtown. The area was overcrowded, politically divided, and poor. Yet it was also a cultural melting pot. Street dances blasted American R&B, ska bands rehearsed in yards, and young people honed their talent in friendly rivalries.

Bob Marley later described Trenchtown as a kind of “university,” where life itself was the teacher. What looked like hardship from the outside became fuel for creative fire. The Wailers’ early songs were not abstract; they came directly from the sound and struggles of the neighborhood.

Early Sounds: Ska, Rocksteady, and Studio One

The Coxsone Dodd Era: Crafting the Sound

To make a name in Kingston’s music scene during the 1960s meant passing through Studio One.

Clement “Coxsone” Dodd’s studio was Jamaica’s Motown, where many reggae pioneers recorded their first tracks. When The Wailers stepped into Studio One, they were still raw. Yet Dodd saw potential.

Backed by professional musicians, they recorded “Simmer Down.” The single spoke directly to Kingston’s restless youth, urging peace during a violent time. It hit number one in Jamaica. This moment established the Wailers firmly in reggae history. Their music wasn’t escapist; it was born of the streets, offering both reflection and warning.

Rastafari and The Wailers: Faith Meets Music

The Wailers were not just entertainers; they were messengers of a faith. The growing Rastafari movement shaped their lyrics, appearance, and beliefs. Dreadlocks, ital living, and the red-gold-and-green flag were not just fashion statements; they were expressions of spiritual conviction

- Bunny Wailer embraced Rastafari most deeply, later leaving the band partly because its grueling international lifestyle conflicted with his spiritual priorities.

- Peter Tosh blended faith with militant resistance, framing himself as a warrior-prophet.

- Bob Marley took Rastafari to the world, softening its edges just enough to reach broader audiences without abandoning its essence.

Their collective embrace of Rastafari turned The Wailers into more than musicians; they became cultural ambassadors.

The Upsetter’s Influence: Lee “Scratch” Perry and the Black Ark

By the late ’60s, The Wailers connected with producer Lee “Scratch” Perry, whose Black Ark studio acted more like a laboratory than a traditional recording space.

Perry’s sonic experiments gave their music a haunting quality. Songs like “Soul Rebel” and “Small Axe” demonstrated a stronger sense of self. “Small Axe,” with its image of the little blade chopping down the “big tree,” became a rallying cry.

The Upsetters’ backing gave the songs a heavier groove, with the basslines practically breathing. Many fans and critics argue that during this era, The Wailers’ reggae music legacy was at its most fearless—political, uncompromising, and spiritually resonant.

Political Fire: The Wailers and Jamaica’s Turbulent 1970s

Jamaica in the 1970s was politically explosive. Rival parties, the PNP and JLP, clashed violently, and musicians were often drawn into the conflict.

The Wailers’ songs became part of that moment. Get Up, Stand Up wasn’t just a metaphor; it was a literal call to resistance.

Marley’s 1976 Smile Jamaica Concert, intended as a peace gesture, occurred just two days after he survived an assassination attempt at his Kingston home.

Where Tosh openly criticized the system in songs like “Equal Rights” and “Downpressor Man,” Marley leaned toward messages of unity and healing. But both were political in their own ways, and The Wailers became the soundtrack of Jamaican struggle.

International Breakthrough: Chris Blackwell and Island Records

When Chris Blackwell of Island Records signed The Wailers in 1972, reggae was still a niche outside Jamaica. Blackwell envisioned something different: presenting them as a rock-style band to international audiences. This move was risky. Some Jamaicans worried the music was being altered for foreign ears. Yet it paid off by opening doors that local producers could not.

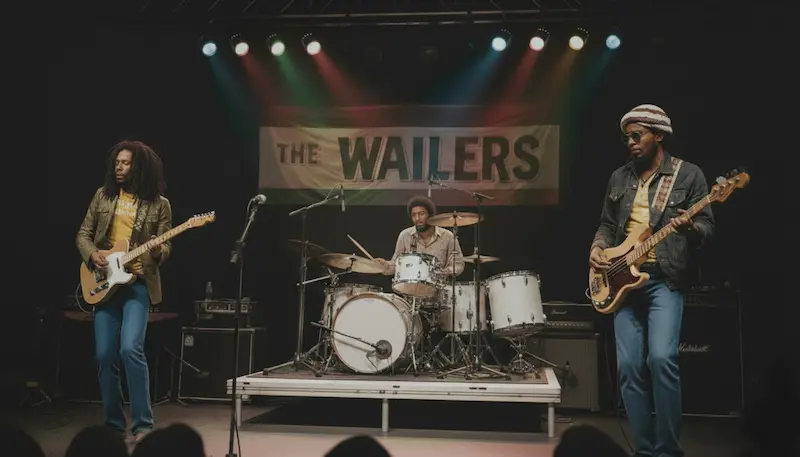

Catch A Fire & Burnin’: The Albums That Lit the World

The first two Bob Marley & The Wailers albums with Island, Catch A Fire and Burnin’ (both 1973), changed the course of popular music.

- Catch A Fire featured haunting anthems like “Concrete Jungle” and the seductive “Stir It Up.” Its Zippo-lighter-shaped sleeve signaled an intent to stand alongside rock records of the time.

- Burnin’ was fiercer, containing “Get Up, Stand Up” and “I Shot the Sheriff.” When Eric Clapton covered the latter, Bob Marley and the Wailers songs reached millions who had never heard reggae before.

With these albums, The Wailers proved reggae could travel far beyond Kingston’s dancehalls without losing its fire.

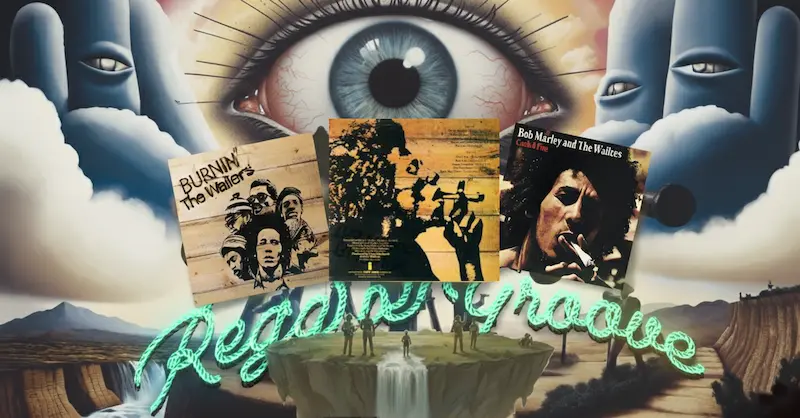

Behind the Music: The Sound of The Wailers Band

It’s easy to think only of Marley, Tosh, and Bunny, but the heartbeat of The Wailers came from its rhythm section.

- Aston “Family Man” Barrett on bass provided the rolling, hypnotic lines that defined reggae.

- Carlton Barrett on drums crafted the iconic “one drop” rhythm, a minimalist beat that carried enormous weight.

Without them, Marley’s anthems might never have found the same groove. Their style was so influential that hip-hop producers later sampled it, and countless reggae bands worldwide copied it.

The Disintegration of the Trio: Solo Paths and Enduring Legacies

By 1974, tensions within the group led to a split. Constant touring, uneven pay, and differing visions strained their unity.

- Peter Tosh went solo, producing albums like Legalize It, sharpening his militant reputation.

- Bunny Wailer leaned into deeply spiritual and roots-driven works such as Blackheart Man.

- Bob Marley, keeping the band name with new members, carried the message to stadiums around the globe.

Bob Marley and The Wailers: A Global Phenomenon

With Marley leading and musicians like Aston “Family Man” Barrett anchoring the rhythm, the new lineup of Bob Marley and The Wailers became synonymous with reggae itself.

Albums such as Natty Dread, Exodus, and Uprising turned Marley into a figure similar to a prophet.

The live shows were electrifying—half church service, half political rally. By Marley’s death in 1981, the band had etched itself permanently into world music history.

The Women of The Wailers: Rita Marley and the I-Threes

Often overlooked in Wailers band history is the role of the I-Threes: Rita Marley, Marcia Griffiths, and Judy Mowatt.

Their harmonies softened Marley’s militant edge without dulling it. Songs like No Woman, No Cry and Three Little Birds carried their warmth. Rita Marley, in particular, was more than a background singer—she was Marley’s partner in life and faith, helping to keep the flame of Rastafari alive through her career.

The Wailers on Tour: Taking Reggae to the World

Touring was where Bob Marley and The Wailers cemented their reputation. In Europe, audiences welcomed them with enthusiasm usually reserved for rock bands. At London’s Rainbow Theatre in 1977, Marley performed through illness, delivering one of his most memorable sets. In the U.S., the breakthrough was slower, but after Clapton’s success with I Shot the Sheriff, doors opened. Suddenly, reggae was on American radio, and The Wailers’ reggae music legacy spread to college campuses and activist circles.

The Wailers in Popular Culture

Decades later, The Wailers’ influence remains pervasive. Their songs appear in films like I Am Legend and Cool Runnings, sports stadium chants, and political rallies.

Few bands in history have had their music adopted so widely across different contexts. “Redemption Song” alone has been sung at funerals, protests, and even political inaugurations. That kind of reach is rare in music, showcasing how deeply Bob Marley and the Wailers songs resonate.

Continuing The Legacy: The Wailers After Marley

Marley’s death in 1981 could have ended the story. But various lineups of “The Wailers” have continued, led by musicians like Family Man Barrett and Junior Marvin.

These later incarnations spark different opinions. Some see them as keeping the flame alive, while others feel they are capitalizing on a sacred name. Still, they ensure that new generations hear the music live, maintaining The Wailers reggae music legacy in circulation.

The Wailers’ Immortal Legacy: More Than Just a Band

Their Ongoing Influence on Modern Reggae

It’s tempting to let Marley’s shadow define the story, but The Wailers were always larger than one man. Their influence spans decades, genres, and continents.

Today, reggae artists, from Jamaica’s revivalists to global fusion acts, still acknowledge The Wailers’ legacy. Hip-hop producers sample them. Punk bands credit them for their rebellious spirit. Even pop stars borrow their rhythms.

At heart, The Wailers were not just a band. They were Trenchtown reggae pioneers, voices forged in hardship and lifted by harmony, who carried local struggles onto the world stage. Their story is inseparable from reggae history and The Wailers’ legacy.

FAQs About The Wailers

Who were the original members of The Wailers?

The original trio was Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, and Bunny Wailer. They began singing together in Trenchtown in the early 1960s.

What caused Bunny Wailer and Peter Tosh to leave the Wailers?

Both left in 1974 due to disagreements over money, relentless touring schedules, and creative direction.

What are the most famous Bob Marley and The Wailers songs?

Classics include “No Woman, No Cry,” “Get Up, Stand Up,” “I Shot the Sheriff,” “Redemption Song,” and “Exodus.”

How did The Wailers influence reggae history?

They transformed reggae from a local Jamaican style into a global voice for resistance, spirituality, and cultural pride, inspiring generations of musicians.

Did The Wailers invent reggae?

Not exactly—reggae grew from ska and rocksteady with many contributors. But The Wailers were the group that brought reggae to the world stage.

What instruments defined The Wailers’ sound?

The Barrett brothers’ bass and drums provided the “one drop” rhythm, while guitar skanks and organ shuffles completed the groove.